Among the Cliffs of the Northwest Spur

Download PDF of essay

MPG V2.8, January 2013

Introduction

Bailey Willis was a geologist with the Northern Pacific Railroad assigned to conduct a reconnaissance of the extent of coal and iron ore in several states, the last being the Washington territory in 1881-1884 (statehood granted in 1889). One of the areas he investigated was the Carbon River and Mowich River valleys where the towns of Carbonado and Wilkeson, among others, were established along the railroad lines for the timber and coal.

In 1882-1883 Willis made expeditions into the upper Carbon River and Mowich River basins, establishing the first trails into the northwest area of Mt Rainier, stretches of which would become the Carbon River Road and Mowich Lake Road (highway 165). The area would become part of the Washington Forest Reserve in 1893, later Mt Rainer Forest Reserve, and in 1899 Mount Rainier National Park.

From his travels in the northwest area Willis wrote a personal essay, likely never to be published than just a personal expression of his experience and thoughts in the area few people had travelled. He would later guide diginitaries into the area, which lead him and others to introduce the idea of Mt Rainier being designated a National Park after Yellowstone in 1872.

The coal and later timber boom went bust and the towns along the railroad lines faded into remanents. The railroad convinced by Willis and others of the potential tourist business in the northwest area, expended considerable effort for awhile to develop tourism, but the southeast area along the Nisqually River became the popular route especially after James Longmire established a road and accommodations at Longmire for people travelling to the Paradise area to camp or climb Mt Rainier.

The essay covers part of one trip he made in July 1882 to the Mowich Lake area visiting Tolmie Peak, Eagle Cliffs and the southern edge to Spray Park and the North Mowich glacier. It should be remembered there were no trails in the area and the only people who preceeded him were occasional indians, a few miners and the Tolmie expedition in 1833.

Notes on Essay

The essay Bailey Willis wrote was transcribed from a copy of the original essay (courtesy of the Huntington Library). Some of the names of the places identified in the essay have been changed. The official name is included in brackets. The most noted is the use of Mt Tacoma instead of the official name of Mount Rainier. Every attempt was made to use the original words than modern usage. Any errors in the text are mine and not anyone else.

In reading the essay it's clear that some of the places identified in the essay are not correct with later information and maps. It should be remembered it was 1882 when few white people had travelled in the area of Mt Rainier where there were no maps and only one's experience and observations as a guide.

Besides the using a different name for Mt Rainier, Willis misidentifies the Mowich glaciers and rivers as the source glaciers and headwaters of the Puyallup River which originates from Sunset Amphitheater in the southwest part of the NP. It's not clear if he is identifying Edmunds Glacier as the South glacier or the actual South Mowich glacier. In addition Crater (Lake) was changed to Mowich Lake.

Among the Cliffs of the Northwest Spur

Bailey Willis, 1882

The rainy season of Puget Sound, the big bear of the new corner, the native element of the old settler, is a snowy one in the Cascade Range. Even on the lower passes, three thousand feet above the sea, the snow falls heavily as trees, chopped off twenty feet from the ground by frosties, making the winter passage of the mountains bear witness.

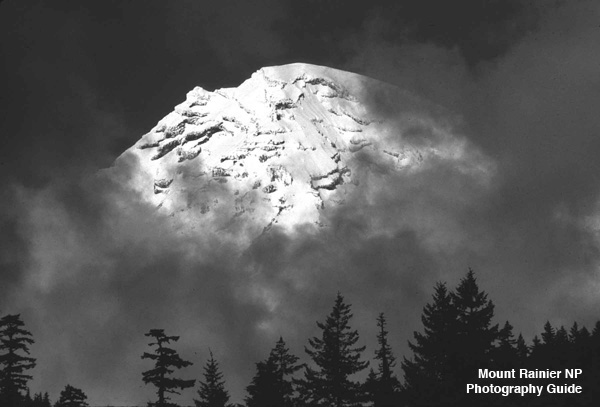

What must be the thickness of the crystal coat on the culmunating summits, on Mt. Tacoma [Mt Rainier] peak, eight thousand fee above the highest crest of the main range. From November to May the flakes settle silently on the Dome, the Liberty Cap and the South Peak; the last arrivals dancing wildly in the winds, drifting into cravesse and corner, or streaming out in clouds to fall wildly scattered over the lower slopes. These snow clouds in winter and the mists formed under the brillant summer sun are the barriers, well known to all, who have watched the mountain from the [Puget] Sound. Just touching the extreme summit the flying sand reaches out horizontally to the leeward for a mile or more; apparently a web of vast strength firmly anchored in the hurricane, in reality a film, ever dissipated, ever renewed.

In the intervals between the storms the noonday sun and the night frost hinder the wind carved surface into gleaming ice crust. Storm after storm add its contribution and the snow covering deepend through the winter months, to be again demolished with the advent of Spring's warm winds and the summer's rains. It is however, but a small frost of the wind driven flakes that escape from captivity with the change of one season; closely packed the masses linger balanced on the high slopes above the black jutting crags, toward which they are inevitably forced.

How long may it be since their atoms danced merrily in the sunlight, that now form yonder snow cliff, two hundred feet high, hanging on the brink of that rock precipice. They have been buried in darkness, till the cravesse opened, dividing those that should go from these the might remain a little longer, and their brothers took that tremendous leap, a thousand feet over buttress and cliff, torn by jagged pinnacles, tossed in whirling eddies by the rush of their own fall, plunging down, down with the war respose the glacier below.

It is but and instant of intense energy, the transition from years of quiet in the great snowcap to hundred of years of resistless march in the ice mass of the glacier.

The downward path is a rugged one; a fall of six thousand feet in three miles. Breaking into pyramids and wedges, a hundred feet in height, on the edge of a hidden declivity, the crystal ice flows onward, unites again, again to shatter into a thousand pinnacles, now spreading out, now narrowing in, as the banks require.

A plastic mass of rigid material. The ice storms linger a year on the edge of a cliff, the warmth of the valley has loosened their bonds, their fellows slip away in muddy rivelets, and they themselves dash down at last, scattering over the morraine below, to join the wild torrent in the rush to the sea. Away through forest, cañon and field to the ocean, to purity and freedom once more. Of all six or eight glaciers that scores the sides of Mt Tacoma [Mt Rainier] there are three better known, the Carbon River glacier on the north, the North and South glacier of the Puyallup [Mowich] on the northwest; all fed by the snows of Liberty Cap. The knife like combs of the rock divide the smooth white mantle, like inevitable fate; alloting to part the slide of the avalanche response of the South, or the lines leap of a thousand feet repose of the North glacier, to the rest that awful plunge of six thousand feet into the basin of the Carbon River.

Then spreading into a wide rugged spur of the mountain, the comb forces the ice rivers and their steams farther and farther apart, till far beyond its reach in the lowlands, they unite once more to join the ocean.

The highest point in the northwest spur, not part of the great mountain mass, is Tolmie's Peak, so named because it was ascended as far back as as 1833 by Dr. Tolmie of Victoria, B.C.; the summit crag is about 6,300 feet above the sea and its ridge, half a mile east and west, reaches six thousand. From it the eye may sweep the horizon from Mt. Baker, on the north, and westward over the [Puget] Sound country to the Olympic Range and thence southward over the wooded foothills to [Mount] St Helens and Mt Tacoma [Rainier]; where to the east mountain peaks rise in stupendous cliffs from gloomy cañons, mountain wall on mountain wall in wild confusion.

A small lake [Eunice Lake] nestles in a depression on the south side of this mountain, at an elevation of 5,700 feet, and a sparkling stream bounds from its outlet in many cascades down the steep slope to a valley thirteen hundred feet below, where grassy meadows are sunk deep among the tall evergreens.

With the thought that the brooklet loved these mimic pastures with a memory of its alpine home, where the flowers deck the rock ledges in scarlet and purple and white, we named it Meadow Brook [Creek].

Early in July a party camped one night on the slope by the lake. Its surface was still frozen and snow drifts were deep around the grass plot, on which the camp fire blazed brightly. The moonlight shone at midnight repose three mummy-like figures, each tightly wrapped in a single blanket with feet turned to the scarce glimmering embers.

A sound like the roar of a great city rose from the cañon below, the mangled voices of a hundred waterfalls. Against the dark metallic sky, from which the stars stood out in relief, the black crags were dimly visible; above them rose in distinct gleaming snow slopes, higher still and higher to the mountain summit.

The great shining peak hung like a phantom above the abyss of darkness; the one pure, bright etheral; the other deep immeasureable, the abode of evil, the gulf of dread. Over powered with a sense of vast space, filled with indifferent power, the watcher slept.

The moon passed on and paled before the growing light of day. The mountain reached out great ribs of snow and rock, and took its stand in the depth of the chasm. The morning stars shone brillant in the eastern sky and a blush touched the beautiful summit. It spread and passed down, leaving a golden spire in the heavens. And as the rosy zone descended over the forbidding precipice and icy slope they melted into fairy land. A vail of opalescent mist enveloped the mountain and the sun rose repose an enchanted world.

A mile south of Tolme's Lake [Eunice Lake] perched on the other slope of the valley of Meadow Brook [Creek] at an elevation of five thousand two hundred feet is another lake [Mowich Lake], half a mile in diameter with an outlet southward into the Puyallup [Crater Creek into North Mowich River]. It too was frozen over early in July and the flowers about it blossomed among the snow drifts; but two weeks later not a vestige of ice remained and the banks of snow were melting fast.

These lakes are curious features of the landscape; filling basins of unknown depth on the steepest slopes. They were once a lake of fire, the northern throats of the great volcano. Gaze down into the depth to day; they are dark and cold, the clear water laps repose the rock bank, on the snow drift dipping in to it, while you lie repose a bed of blooming heather, amid countless white with golden stamens, and rejoice on the warm sunshine.

What a change since the fiery floods poured forth, perhaps simultaenously from the three craters, that here within a square mile, drowning the valleys and their streams, the mountains and ridge, out over the luxuriant growth of coal measures of that period, levelling all in the great slope, from which peaks and cañons to day are carved. Crater [Mowich Lake] quickly suggested itself as the appropriate source of the largest and last mentioned of these basins.

It is but little worn by erosion, the outlet into the Puyallup [Crate Creek into North Mowich River] being only a hundred feet below the rocky saddle that prevents it from emptying northward into Meadow Brook [Creek]. On the southeast is a bold slope of a thousand feet up to the crags [Castle Peak], that bound the third crater [unnamed lake southest of Castle Peak], and on the south a single precipitous point [Fay Peak] stands sharply against the sky about fifteen hundred feet above the lake.

From these cliffs a shout is mockingly passed on around the circle, repeated six or eight times, dying away at the last in the distance like laughter.

The sight of Mt Tacoma's (Mt Rainier's) great cap, but six miles away, rising above the trees near the outlet will inspire the least enthusiastic to an attempt at the nearer acquaintance. Following around the wooded hillside for a mile, he will come out on the brink of a precipice [Eagle Cliff] twelve or thirteen feet high. In the valley below, the muddy torent of the North Branch of the Puyallup [North Mowich River] tumbles over boulders of the great terminal moraine of the North [Mowich] glacier.

A mile away, nearly on the level with your eye, is the dark brown face of the glacier, two thousand feet across and a hundred feet high. Back from it, the ice rises gently for perhaps a mile, a tongue like flow, which shows in the diverging crevasses the lines of its movement. Above, where the glacier descends more boldly, the ice blocks flash back, the sunlight, glowing as they glowed a thousand year ago on Liberty Cap, where the shining crystals now hang, that must in time follow down the rocky path.

Pass along the edge of the precipice toward the mountain, cliffs hang out above you and the gulf still yawns below; but there is no danger for an active climber and indeed secure horse trail may be built for another mile along the mountain side.

The rocks at last give and form an amphitheater, whose rugged walls are four hundred feet high; above a long slope of loose fragments. Hidden precipices till now from human eyes, are two beautiful waterfalls [Spray Falls], the one however, but an accessory to its grand companion. The black skyline of jagged rocks is hidden by the tossing mass of foam, which dashes from ledge to ledge for seventy feet before it separates; then spreads in sheets and filaments; these here leap boldly out to be lost in the mist before they each reach the bottom, those there, clinging to the rock, clothe it with snowy gauze and only leave it at last, where it overhangs, a hundred feet above the pool below. The total height of the fall is something over three hundred feet and the stream at the summit is perhaps thirty feet across; below it is lost among the debris of the cliff and runs in many sparkling brooklets toward the next plunge.

Half a mile beyond there is a second amphitheater, in which there are again two falls [unnamed creek and waterfalls east of Spray Falls], but of less volume and depth of leap than the first.

Here we paused; the golden gleam on Mt Tacoma [Mt Rainier], warned of the approach of night. Though but a half mile from the glacier, on which we had hoped to be the first to set foot. We turned away perforce and hurried back to Crater [Mowich Lake].

The gleam of the moonlight played that night north the glow of the camp on the placcid surface, and the tall rocks and trees gazed down into its depth, whence their own perfect image was reflected.

Additional Notes

In 1882 and 1883 Bailey Willis guided dignitaries on trips into the northwest area of now Mt. Rainier NP, but this essay doesn't indicate if this description and narrative of a trip in July 1882 was one of those trips or just one of the several he made into the area during those years.

It's been noted that based on Dr. Tolmie's notes he didn't quite reach the top of Tolme Peak but reached the ridge line to the top, which is east-northeast of the lookout. No information exists on the weather in July 1882, but it's not unusual for snow to linger in the Mowich Lake area in early July, even in recent years.

The route to Eagle Cliff and Spray Falls is very close to the trail hikers take now from Mowich Lake to Spray Park and Spray Falls. It's very possible Bailey Willis and others were the first to see Spray Falls and the falls east of Spray Falls.

It's clear Willis identified "the Puyallup" as what is now the North Mowich River. This is due to the fact there hadn't been explorations into the upper Puyallup River basin to discern the larger basin of Puyallup River is the southern part of the basin and the Mowich River basin is the smaller, northern part of the basin

Bailey Willis' experience in the northwest part of Mt Rainier NP would prove invaluable in 1896 when he and a team of geologists and others made a two-plus week expedition to the area and across the northern side of Mt Rainier where they made a base camp along Winthrop glacier. Willis and others made a summit climb, spent the night, went down to campers at Paradise, and returned to the base camp on the eastern side before heading back to the Carbon River area and to Tacoma.

The report of the expedition, published in 1898 by the US Geological Survey, became part of the final pieces of the effort to pass the bill in Congress to designate Mt Rainier National Park which was signed by the President in March 1899.

Please use the contact link to send e-mail.