Mt. Rainier NP Overview

Find areas via a

map or

guide

MPG V2.8, January 2013

Background

There is nothing I can write that hasn't already been written or said about Mt. Rainier and the National Park (NP). I can, however, provide some information about the mountain and the NP which might help your experience and photography in the planning and preparation of your visit and your experience of the NP during your visit.

This Web page will present some general and interesting information while the photo guide will present Web pages on different topics and activities about Mt. Rainier and the NP and the area guides will present additional details on the different topics and aspects for each of the five areas of the NP used in this guide.

While the information presented on the Web pages is useful for visitors, for which much of it is intended to enhance your understanding and experience, it is primarily focused on photographers to provide the wealth of background and additional information and resources for your photography interests and work in the NP.

And while it is useful for any photographer, and even the occasional or amateur photographers, much of it will be focused on the serious, professional and commercial photographers who have specific interests and goals with their work to need more extensive and detailed information for their visit, and either hasn't been to the NP or has specific time constraints.

And while it is far from complete information for even those photographers, the goal here is to provide the essential information, resources and references to help with the planning and preparation with their trip. As such, the information will be updated as appropriate and with new or expanded sections as information is found or available.

One goal with the whole suite of Web pages will be on-line chapters and sections in PDF files to facilitate saving, printing and use in the field. The longer term goal will be a book with the basic information and maps which don't change significantly with the recent and latest information link to the book on the Website.

History

Mount Rainier was designated a National Park in 1899, the fourth in America's history. The effort to win the designation took almost eight years, the Congressional work going back to 1892, and the effort before that into the 1870's when the first mountain climbers saw the need to save the area as a national park. An extensive history of the NP was researched and written by NPS historian Theodore Catton

In the end, it took three groups to get the bill passed through Congress to the President who was waiting for it. The previous President saw the need to preserve the land, and noting the initial problems getting it designated a NP, chose to set it asides as a Forest Reserve. From this larger area of land, the NP with it initial square boundaries was designated in 1899.

The effort to pass the bill was the work of the mountaineering and recreation community, the local commercial and civic organizations, and governments, and the scientific community. It was this last group, with the effort and work of the US Geological Survey, much from their expedition in 1896, which won the day for the NP.

What has gone mostly unnoticed through the work describing the effort to get the NP designation were the photographers. In 1890 Kodak introduced the first sheet film, a nitrate back 4x5 black and white film. This exploded the use of film in photography and opened the door to the number of photographers working in and around Mt. Rainier before 1900. Their work in print showed the sheer beauty and scientific value to everyone, especially those in Congress.

After the designation, it took another decade to get sufficient funds to actually manage and operate the NP, and to begin the development for the visitors as the trip itself was an adventure by train, wagon, mule and walking. What we do now in 1-2 hours took the better part of 2 or more days to get to Paradise.

While work was done by other agencies to improve the access to Longmire and Paradise, much of the NP remained as it was when it was designated. It was the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916 and the operation and management of all NP's when work really began to be focused and completed for the new number of visitors coming to the NP.

Several things were then accomplished which made it a better experience for the visitors. These were the first road all the way to Paradise, the completion of the initial Wonderland trail, which is almost the same as today, the construction of the Paradise Inn and National Park Inn (Longmire) replacing all the tent cities, and the construction and formal organization of the mountain (summit) climbs with guides, registration, etc.

From there, and with the first topographic map of the NP in 1915, the NPS improved the access, trails, facilities, rules, etc. for the visitors, hikers, mountain climbers and photographers. From there, things have only improved for everyone. The NP was expanded in the 1930's on the eastern boundary to the crest of the divide of the Cascade Mountains and in the southeastern corner for the Backbone Ridge and highway.

Information

Mt. Rainier NP is located south of Seattle and southeast of Tacoma, Washington, on the western side of the Cascade Mountain Range. The eastern boundary of the NP is the crest of the divide of the Cascade Mountains from the southeast corner north to and along the divide with Silver Creek (Crystal Mountain Resort) to the white River in the northeast corner.

Almost all the rest of the boundary are straight lines corner to corner, on northern boundary (northeast to northwest corners) and western boundary (northwest to southwest corners with a few jogs along this line). The southern boundary follows the Nisqually River from the southwest corner to the Pierce-Lewis County line, then following the county line to the southeast corner, as does the northern boundary which follows the Carbon River for some distance in the northwest corner.

This wasn't the original boundary defined in the original Act of the NP designation in 1899 which established a boundary thought to be square within the Mount Rainier Forest Reserve. The current boundary was established in 1931, see laws governing the NP, to better manage the land around Mt. Rainier putting the entire upper river basins draining the mountain into the NP. This also helped coordinate and manage the road system in the NP with the State of Washington, Pierce County and the NP.

Getting There

That said the first question visitors usually ask is, "So, how do I get to the NP?", like I should have already answered that. You can get a NP travel guide and a park guide with descriptions of the roads and highways and the access with links to maps of the area and NP.

You should review the various travel guides available in books and through a Google search to determine which areas you want to visit within the time for your travel and visit. All the entrances are 1-2 hours drive with up to an hour in the NP to the trailheads, campgrounds and visitor areas. And it's always slower and busier during peak visitor days during the summer, especially weekends.

Presence

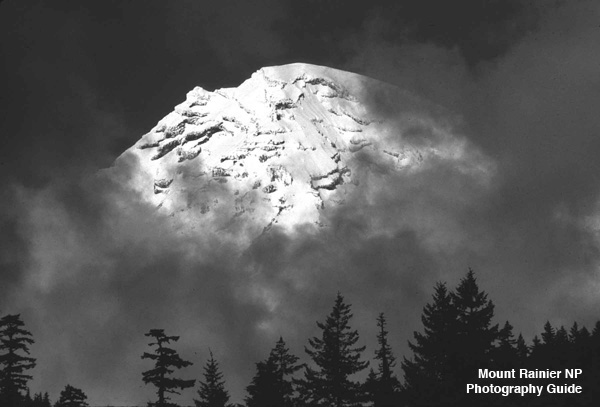

So the next question is usually, "So, what can I see there?" Beside the sheer beauty of Mt. Rainier and the majestic and scenic lanscapes and the original old growth forests of the NP?

The most obvious feature is Mt. Rainier itself, the tallest and largest of the volcanos in the chain of volcanos sitting atop the Cascade Mountain Range from Mt. Baker in north to Mt. McLoughin in the south. It was the sheer presence of Mt. Rainier which drew the indians to its slope for thousands of years for food, resources, and simply recreation (sorry, we didn't invent recreation at Mt. Rainier) and drew the first explorers who sailed into the Puget Sound.

Mt. Rainier was evident on the southern horizon when the first explorers sailed through the Strait of Juan de Fuca and turned south into the Puget Sound (present day Port Townsend) and saw this majestic mountain in the far distance. And once the settlements and forts were established, it wasn't long before they wanted to explore Mt. Rainier, from the first trips on the upper slopes in the 1830's to the first successful summit climb in 1870.

It was the period after the first the summit climb which accelerated the number of visitors and the interest to designate it a national park, which culmunated in the passage of the bill in 1899, the work of the mountain climbing and recreation organizations, the local civic organizations and governments, and the scientific community, especially the US Geological Survey.

Environment

Mt. Rainier is evident when you visit, on any a clear day around the Puget Sound. And on those days it dominates the southern landscape and your view. And the obvious which features stand out are the volcano itself, the snow and glaciers, and the surrounding forest. It only becomes bigger and better the closer you drive toward it.

Volcano.-- Mt. Rainier is a stratovolcano, one built from many layers of lava flows from the large chamber underlying the mountain. It wasn't however, a single vent volcano as there are smaller vents now dormant and buried under later flows on the slopes around the mountain.

In addition, eruptions of Mt. Rainier have deposited ash and debris on the slopes of the mountain along with the ash from eruptions of other volcanos in the Cascade Mountain Range, including the famous eruption which created Crater Lake in southern Oregon. The eruptions of Mt. Rainier, however, have not been significant compared to those of other volcanos, including the eruptions of Mt. Rainier in the 1850's and 1870's. But it's the many smaller eruptions of Mt. Rainier over its life which have deposited extensive layers of ash and debris around the mountain.

Surprisingly Mt. Rainier isn't an old volcano, the original cone is only a few hundred thousand years and the current mountain is less than ten thousand years old, from the last stage of continental glaciation in the Puget Sound (Vashon Stage). In short, what you see today is relatively new mountain, geologically speaking, sitting on top of layers of and old volcano and volcanic flows on top of the Cascade Mountain batholith.

In addition two mass wasting processes have severely changed the new cone when it emerged from the last glaciation and created the new volcano. At its peak Mt. Rainier was about 2,000 feet higher and more traditionally shaped for a stratovolcano. Remanents of that cone exist today in some of the high elevation rock masses, such as Little Tahoma.

The first and largest was the Oscela Mudflow about 5,700 years ago when much of the northeast and east face of the mountain collapsed and the mass of the material from the summit and the slopes flowed down the White River to the Puget Sound between Seattle and Tacoma, filling the valley with hundreds of feet of debris. Many other lesser lahars and mudflows have also reshaped the mountain since then.

The second process is the many glaciers on the slopes of the mountain. They are nature's tool which constantly erodes and transports material of the mountain down the glaciers and rivers eventually into the lower valleys. As the mountain's volcanic process builds the mountains the glaciers and occasional lahars and mudflows erode it.

In the end, Mt. Rainier has a geologic problem. It does not have a lot of hard rock inside it and it's been thoroughly penetrated by water over its geologic history. As one geologist said, "It's a mountain of mush.", meaning it's a mountain of very fractured or soft rocks and material with lots of water inside and glaciers outside, and the continuing Pacific Northwest climate with 500-1,000 inches of snow annually.

Glaciers.-- The glaciers are the second obvious and dominant feature of Mt. Rainier. At last count there are 26 recognized glaciers on Mt. Rainier. Eight are considered primary glaciers, six of which originate at the summit of Mt. Rainier. Another ten are considered secondary glaciers and the rest are minor glaciers or more closely resemble snowfields.

Of all the glaciers about half are accessible from one of the many trails in Mt. Rainier ranging from easy day hikes to long or overnight hikes, which are identified on the map for viewing glaciers. These trailheads are scattered around the NP and accessible from any of the different areas in the NP. You can get additional information on the glaciers of Mt. Rainier. And an excellent background on the glaciers of Mt. Rainier is in Carolyn Driedger's book (below), excerpted here and summarized from other reports here.

After the obvious features, from any distance around the Puget Sound, of the volcano and the glaciers, the next feature are the different environment zones, namely the forests, the sub-alpine open areas and meadows, and the alpine ares of glaciers, snow and rocks. These features distinguish the landscape surrounding the mountain and is clear within a short distance from and in the NP.

Environment Zones.-- There are three environment zones in Mt. Rainier NP, the forest, the sub-alpine and alpine zones. The alpine zone is the area of the Mt. Rainier is dominated by the snow, glaciers and rock, from about 7,500 feet elevation to the summit. The forest zone, which has three subzones, is the area in the lower elevations surrounding Mt. Rainier up to the upper limit of trees between 7,000 and 7,500 feet elevation. The subalpine zone is the intermediate zone between the forest and the alpine environments, between 5,000 and 7,500 feet elevation, when extended periods of seasonal snow limits trees for the vast areas of meadows and shrubs.

These zones have distinct characteristics which defines where each varys with elevation by location around the mountain and by the dynamics with the annual weather and longterm climate changes over the area, as seen in the recent years from the effects of global climate change currently under research and discussion.

Forest Zones.-- The forest zone itself is divided into three general forest zones, the lowland forest, the intermediate forest and the subalpine forest. While each zone have distinct trees there are no clear divisions as each type and trees overlap and blends into the other zones by location, elevation and weather.

Lowland Forest.-- The types of trees in this zone is extensive and continuous into the surrounding Cascade Mountains and lowland hills west of the Cascade Mountains and into the Puget Sound region and the Cowlitz River valley. There are, however, a few dominate forest types and trees in each area to establish the climax forest. Overall, the zone extends from the lowest elevation to between 3,500 and 4,000 feet elevation around Mt. Rainier.

Intermediate Forest.-- This forest type fills the range between the lowland forest and the upper subalpine forest, usually between 4,000 and 5,200 feet elevation, but is as low as 3,500 feet and as high as 5,500. A few types of trees dominate this zone, each depending on location in the NP due to elevation and weather.

All the dominant and other trees in this zone are cone-bearing (coniferous) with the exception of a few deciduous species of Willow in the lower elevations. And due to the weather conditions few trees exceed 3 feet in diamater and usually smaller with significantly less ground cover and undergrowth.

Subalpine Forest.-- The intermediate forest usually changes into the subalpine forest, but in some places can change directly into the subalpine (non-forest) zone of open meadows or into the alpine zone of near-permanent snow, glaciers or rocks.

This forest zone is usually found between 5,200 and 6,500 feet elevation and is dominated by a few alpine tree species, notably Alpine Fir and Mountain Hemlock. This is also the zone where you see the deformation of trees due to the wind, snow, temperatures, and other weather factors where existence is difficult at best.

Forest Zone Notes.-- One thing you'll see in the NP are areas of the aftermath of forest fires with cleared areas or dead standing trees. It is the policy of the NPS to let forest fires burn unless the fire becomes too large or endangers surrounding forest (outside the NP), roads or facilities. This is obvious in some areas, such as Grand Park in the northest area northwest of Sunrise.

Sub-Alpine Zone.-- Between the forests zones and the alpine zone of snow and glaciers is the sub-alpine zone with the extensive areas of low lying shrubs and meadows. Examples of these areas are found at Paradise Park, Indian Henry's Hunting Ground, Spray Park, Summerland and the Yakima area at Sunrise.

This zones ranges from about 4,500 to 7,000 feet elevation, reaching to the extreme limits of vegetation and the margins of perpetual snow. This is where the long season of cold weather, both temperatures and extended snowpack, usually October to July, limits the size and spread of vegetation and accelerates the short growth and reproductive season.

All the species are sub-alpine varieties of trees, shrubs and flowering plants, the trees commonly being the Alpine Hemlock and Alasks Cedar which withstand the weight of long periods of snow. It's also where you find the trees contorted by wind, ice and snow, often breaking or splitting and regrowing from the remanent trees, and where you find stunted trees in tight clusters.

Alpine Zone.-- Above the two lower zones is the alpine zone. It is easily identified by the absences of vegetation and the presences of glaciers, permanent snowfields, snow and rocks. It's the upper zones where the snowfall accumulates for the source of glaciers and partially determines the mass of the snow for the equilibrium line (division) between the accummulation and ablations zones of glaciers.

It's also where the rocks are evident despite the sheer volume of snow, where snow can't accumulate due to the steep slopes of the ridges of rock outcrops on the mountain. This includes the actual rim of the summit crater and the many steep and vertical sides of rock such as Tahoma, Success Cleaver, Cathedral Rocks, among others. Many of these are old volcanic flows their sides long eroded by glaciers.

Photography

Before you go to Mt. Rainier NP, it's best to sit down with some maps of Mt. Rainier NP, and some travel and visitors guide books. The Park is large as it's a 1-2 hour drive to any of the entrance from Seattle, see travel overview, with additional driving to visitor centers or trailheads. During the tourist season, Memorial Day to Labor Day holidays, the NP is busy with many parking and trailheads full early in the day, and there are restrictions and fines for parking outside designated areas.

Once you are basically familar with the National Park, then you can begin to plan the places for your visit and photography work. To help with this, I have divided the National Park into five areas, which are the White River-Sunrise Entrance in the northeast quadrant, the Cowlitz River-Packwood entrance in the southeast, the Nisqually River Entrance in the southwest, and the Carbon River-Mowich Lake Entrance in the northwest, adding the Paradise area as a separate area.

Each of these areas are accessible by different highways, with only two connecting highways, one north-south in the eastern quadrants and one east-west in the southern quadrants. This means you can do an all day car trip through three of the quadrants, stopping at the visitors center at Paradise, all of which are described on the road trips Web page with map locations for stops, places, etc. If you plan to do any short hikes in the NP you can check the dayhike Web page. If you plan longer day hikes, you should be prepared with a day pack and the outdoor essentials.

Once you become familar with the NP and its sheer wealth and diversity of photo locations and opportunities, you need to determine what areas and subjects you want to focus on during your visit and for your work. You can get more information about subjects and activities from the resources listed at the bottom of this Web page, along with more detailed information about the five areas of the NP.

Mt. Rainier has four distinct seasons. Not surprisingly summer, which is Memorial Day through Labor Day holiday weekends, is the busiest for the NP for the plants and animals and for the number of visitors. The other three seasons, however, each offer their own unique photo locations and opportunities if you are prepared for the weather and conditions and flexible with your plans.

Photo Ops

The photo opportunities are pretty much up to you. There's no limit, just the time you have to explore and photograph all of them. But that said, it can be summarized (aww the photo places Web pages.

The most popular entrance is the White River entrance, the closest to Seattle. This is also the road to the Crystal Mountain Ski Resort before the entrance to the NP. The highway continues along the NP to Chinook and Cayuse Passes and to Highway 123 to the the Ohanapecosh Entrance and the Stevens Canyon highway to Paradise.

There are numerous trailheads off the highway from the White River entrance to the road to the Sunrise visitors areas or highway 410 and onward to Chinook pass, where you can drive over Cayuse Pass to eastern Washington or onward on the highway to more trailheads. There are numerous trailheads on Highway 410 from the NP entrance to Cayuse Pass, many with turnoffs for views and short hikes to panoramic views of Mt. Rainier.

Additional information on the Sunrise Area provides lots of photographic opportunities, many of which are accessible via short hikes. It is highly recommended to understand and use the hiking tips for your hikes.

The next most popular entrance is the Nisqually entrance, the closest to Tacoma. This entrance has more visitors areas including the shortest drive to Paradise. However, many of these areas were severly damaged in the November 2006 and later storms and floods, and won't be repaired or rebuilt, such as the Sunshine point campground. But that said, it shouldn't discourage a photographer from visiting these areas.

The first area just inside the Nisqually entrance is the Sunshine campground where you can get good views of the Nisqually River and the forests in the NP. This place also affords a great place to access the lower Nisqually River area and trailheads. The second area is the Westside Road, which is a trailhead to many other trails, such as the Tahoma Creek trail, Gobblers Knob trail and the Puyallup River basin trails.

The third area is the Longmire Area. This also is an excellent opportunity for photographers along with the visitor services available there (hotel, restaurant, store, and visitor center). There are many trailheads at or near Longmire for shorter day hikes and longer hikes into the higher elevations.

The next area is really a road, the road from Longmire to Paradise. There are numerous turnoffs for vistas and viewing, trailheads, and waterfalls. When you plan the trip, it's not unusual to spend the day getting to Paradise along with a day at Paradise, so planning your time is helpful. It's easy to lose track of time at each place and lose track of the time you planned there.

The third popular entrance is the Ohanapecosh entrance, accessible from highway 12 from Interstate 5 between Portland and Tacoma-Seattle. This area is the least visited by visitors because of its inaccessibility from Seattle and Tacoma and from seasonal closures or occasional closures from damage or for repairs.

There is however, some excellent different photographic opportunities from the Ohanapecosh area, and time should be scheduled to visit many of the visitor areas and trailheads. In addition, the Stevens Canyon road offers many vistas, turnoffs and trailheads, including the most photographic place in Mt. Rainier NP, Reflection Lake.

If you plan to photograph Reflection Lake, as they say, timing is everything, and usually the best time is just before or at sunrise, and occasionally sunset. This place is close to Paradise, and accessible from the Nisqually entrance by turning onto the Stevens Canyon highway before reaching Paradise. In addition there are several excellent short hikes between the lake and the highway to the entrance, such as the Box Canyon and Cougar Falls hikes.

The last entrance is the Carbon River entrance, which is close to both Seattle and Tacoma, but only through local highways and roads. Besides access to the Carbon River Road (closed at the NP entrance), you can take the alternate road to Mowich Lake. This area has some excellent hikes and photographic opportunities to upper elevation meadows at Spray Park.

As said the Carbon River Road is closed at the NP entrance, and some of the trail has not been sufficiently rebuilt to be an easy hike. It is a significant hike into the upper reaches, so you have to plan accordingly. And being the least accessed trail, you'll easily have a quiet hike meeting few people with many photographic opportunities of the river and forests. You will need a backcountry permit to camp at the Ipsut campground.

The Paradise visitors area, which is accessible from three entrances but not from the White River entrance at this time and likely well into next year, is the most visited area in the Park. Currently there is limited parking and a shuttle service is available from nearby parking areas. Check the NP shuttle guide.

It's easy to spend the day or more at Paradise where you can stay at the recently remodeled Paradise Inn or at Cougar Rock campground. There are plenty of trails at Paradise, most short to vistas, some longer for seeing the surrounding area, and the trail to Camp Muir.

The trail to Camp Muir is open to all without a permit, but only for the day. You must return. To stay at Camp Muir you must have an overnight permit and understand the special rules that apply. Since it is the most used starting point for summit climbs, you have to consider climbers first in your hike there. But it shouldn't stop you if you are fit. There are many photographic opportunities on this trail.

Before you plan your photo locations in Mt. Rainier NP, there are a number of excellent photography books along with photographers' Web sites in photography guide Web page on Mt. Rainier NP to get ideas of places and photographs. Most good bookstores should have these.

- "Mount Rainier National Park", Pat O'Hara and Tim McNulty

- "Wasington's Mount Rainier National Park, Centennial Celebration", O'Hara and McNulty

- "Color Hiking Guide to Mount Rainier", Alan Kearney

- "Mount Rainier National Park, Impressions", Charles Gurche

- "Mount Rainier, Views and Adventures", James Martin and John Harlin III

Advisories

Advisory about Glaciers.-- There are a number of trails to glacier overlooks and to or near glaciers. Glaciers are inviting to hike and explore, but they are dangerous for the inexperienced and ill-prepared hikers, and as such please heed this advice.

Do not go on a glacier without experienced guide(s) and the proper equipment.

Glaciers are also very dynamic and constantly changing environments, so it's best to view and photograph them, but don't go on them without training, guides and equipment. There are established techniques for glacier travel taught by the companies leading summit climbs, which applies to any high elevation snow environment or glacier.

Advisory about meadows.-- There are a number of trails to and through meadows. They are very inviting to travel off the trail to get some photographs, but it's best to take what photographs you can from the trail or established rest stops.

Stay on the designated paths and trails in the meadows, especially when snow covered.

You may not leave a trace, but others may not be so cautious and careful about their footprint in environmentally sensitive areas. This is especially important in the late snowmelt season where hiking on the thin snowpack can damage the fragile meadows underneath.

Advisory about Guns.-- Beginning February 22, 2010, openly carrying guns in the NP is legal and concealed with a legal permit. However, there are a number of conditions, which you can find here with links to additional information.

It is illegal to carry a gun indoors and it is illegal to use or fire a gun anywhere in the NP.

This is especially important in the visitors areas, the campgrounds, on the trails, and in the backcountry. You can only openly carry a gun or concealed with the proper (state) permit) and nothing else. You can not unholster, use or discharge the weapon anytime or anywhere in the NP. The NPS has trained and instructed the park and backcountry rangers to treat all visitors as if they are carrying a gun unless it is clear the visitor is not carrying a gun.

The last advisory is the obvious. Follow the rules, park where you're allowed, and get permits if required. It's simply being curteous to our national park and the other visitors. And it avoids a conversation with a park ranger and perhaps a ticket.

Personal Notes

The first note is the same as anyone would say, plan well, but be prepared and flexible. And above all, remember it's our National Park, for everyone so take care of it for yourself and all of us. This is especially important in high elevation open, alpine and glacier areas. The environment is easily damaged by abuse and long in repairing itself.

If you prefer to do your hiking solo, that's fine, many people, myself included, hike solo, and it's not uncommon to meet solo backcountry hikers. It's all about your experience and skills, and the degree of trust you put in yourself. And it's more than likely you'll meet other hikers, especially since you have to camp at established campsites for your permit.

Below are sources for additional information about Mt. Rainier and the NP.

- Weather - Map

- Waterfalls - Map and List

- Lakes - Map and List

- Wildflowers - Map

- Fire Lookouts - Map

Please use the contact link to send e-mail.