Glaciers of Mount Rainier

Find view locations via a map

Click for larger map

MPG V2.8, January 2013

Introduction

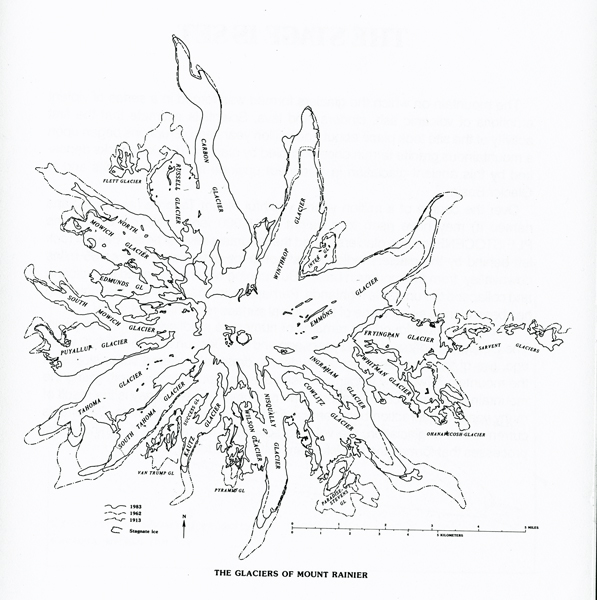

At last count there are 26 recognized glaciers on Mt. Rainier. Eight are considered primary glaciers, six of which originate at the summit of Mt. Rainier. Another ten are considered secondary glaciers and the rest are minor glaciers or more closely resemble snowfields.

Of all the glaciers about half are accessible from one of the many trails in Mt. Rainier ranging from easy day hikes to long or overnight hikes, which are identified on the map for viewing glaciers. These trailheads are scattered around the NP and accessible from any of the different areas in the NP.

Maps

You can download several maps (PDF files) of the glaciers of Mt. Rainier: a basic outline map, the DNR map, and a topo map, along with download the latest USGS 7 1/2 minute (1:24,000) topo maps of Mt. Rainier NP.

Overview

The recent geologic history of Mt. Rainier can be explained by two geologic processes, volcanism and glaciers. These two are inseparable in the formation and continual changes in the mountain. They're always in a dynamic relationship, one building and forming it and one destroying and transporting it, which has lead to the impact of other geomorphic processes, namely, landslides, mudflows, jokulhlaups, and floods which are also destorying the mountain.

You can read the geologic history of Mt. Rainier in the many references in the resources and those listed below. The most important thing here is the recent history which brought about what you see today. And that starts just under 6,000 years ago when Mt. Rainier was about 2,000 feet higher than it 14,410 feet elevation today.

About 5,700 years ago about 2,000 feet of the summit of Mt. Rainier collapsed in an avalanche and a lahar down the White River, known now as the Osceola Mudflow which reached the Puget Sound south of Seattle and Commencement Bay near Tacoma. This left the summit and cone of Mt. Rainier pretty much like it is today.

Additional mudflows, such as the Electron Mudflow, have removed more material from the upper slopes of Mt. Rainier. Smaller lahars, jokulhlaups, and landslides have occurred, even recently, and are always a risk now with Mt. Rainier where a hazard warning system has been established and is operating in the Puyallup and White River valleys.

Background

The glaciers of Mt. Rainier have been investigated since mountain climbers first began exploring the mountain and making summit climbs, but those were incidental explorations and observations by visiting scientists. It wasn't until the 1896 USGS expedition to conduct a reconnaissance of the glaciers and geology of Mt. Rainier that scientific interest became focused on the mountain.

After Mt. Rainier became a National Park in 1899, the USGS followed up with two surveys (1910-1913) of the NP with a full traverse and plane table mapping survey of elevation of the peaks in and near the NP which resulted in the first published topographic map of the NP in 1915. These survey also established the extent of the glaciers down their respective river valleys which was followed up with the 1935 and 1971 maps and with updates in later prints of the maps.

Other scientists began the field study and documentation of the glaciers in the early years of the NP, most of which was focused on the Nisqually Glacier, beginning in 1918, due to the easy access from the road between Longmire to Paradise which required fording of or the crossing over the Nisqually river below the glacier. Previous records of the Nisqually Glacier exists from the 1880's with photographs and reports by local residents.

Other glaciers were also photographed in the 1890's and early 1900's as photography expanded after widespread use of large format (4x5 or larger) sheet film and later Kodak roll film cameras and more trails were developed in the newly established national park and resources were available to construct better roads and trals.

Glaciers

An excellent background on the glaciers of Mt. Rainier is in Carolyn Driedger's book (below), excerpted here and summarized from other reports here. When viewing glaciers a few basic ideas and terminology about glaciers is helpful. The best guide for this is Carolyn Driedger's book (listed below), but I'll present a few basic ideas and terms.

Glaciers.-- Glaciers are the result of a cold seasonal climate with a high precipitation which results in the accumulation of snow on the slopes of mountains. Glaciers occur when the snow accumulation exceeds the seasonal melting, and over years forms glaciers on the slopes.

Once formed glaciers become geomorphic structures in dynamic equilibrium with the mountain and the annual climate and seasonal weather. Simply put, more cold temperatures and snow they grow and less cold and snow they shrink. This is also why the effects of global warming on the weather and glaciers on Mt. Rainier are important to research.

The changes in the temperature and snow are identified in the glacier with two zones, accumulation and ablation. Accumulation occurs on the upper slopes and ablation occurs on the lower slopes, which is what the glaciologists use to determine the mass balance of the glacier. The movement of the equilibrium line between the two zones to used ot evaluate the "health" of the glacier.

The equilibrium line moves down the glacier when accumulation exceeds ablation which results in the glacier becoming thicker and wider in the valley and advancing down the valley. This often tends to reduce the seasonal and annual flow in the river from the glacier as more precipitation is stored in the hydrologic system as snow in the upper slopes in the glacier.

The opposite happens when the opposite conditions occurs and the equilibrium line moves up the glacier. The glacier recedes and becomes less thick and narrower. This could result in above normal flow in the river from melting glacier water.

This is what you see during your visit, the whole dynamic weather, geologic and geomorphic relationship reflected in the glaciers. And tomorrow everything will be different.

Features.-- Not only are glaciers dynamic with the climate (temperature and precipitation), they're dynamic with the mountain. Every aspect of size and shape is also in dynamic equilibrium with the geography, geology and geomorphology of the mountain.

Glaciers are constantly eroding the mountain and transporting the material down the mountain. In this work the glacier transforms the valley creating and removing features. Features during the periods of the greatest extent of the glacier often remains as remanent features, such as moraines, glacial polish and striations.

Glaciers are also transporting material in two ways. The first is seen on the surface of the glacier from the debris collected over time. The second is seen in the meltwater where the flow has a chocolate milk appearance from the fine sediment, or glacial flour, created by the glacier on the mountain's surface.

The last feature are the crevasses. These are created by the movement of the glacier over the underlying mountain features, such as steep slopes, the widening or narrowing of the valley, and bends in the valley. The different velocities of vertical and lateral profiles causes the surface to cracks in the surface creating crevasses.

Glacier Photo Opportunities

Find view locations via a map

Below are the glaciers with trails to access and for viewing the glaciers in Mt. Rainier NP. The list starts in the Paradise area and goes clockwise around the NP to the southwest, northwest, northeast, southeast area glaciers. All trail distances are one-way and rated as easy, moderate, hard or difficult, see rating guide.

Paradise Glacier.-- This glacier is accessible via the east loop of the Skyline trail from the Jackson Visitors Center to the Paradise Glacier trail which begins at the Van Trump Memorial east of the Visitors Center. The trail takes you the terminus of the glacier. It's a 3.2 mile moderate trail.

Nisqually Glacier.-- There are three trails to view this glacier. The first trail is the Nisqually Vista trail from the Jackson Visitors Center. It's an easy 1.2 mile trail west from the Visitors Center to an overlook south of the terminus of the glacier.

The second trail is the Glacier Vista trail. It's a 2.5 mile moderate hike via the west loop of the Skyline trail from the Visitors Center to an overlook to the terminus of the glacier and up the glacier valley.

The third trail is a 1+ mile scramble up the Nisqually River valley from the west side of Glacier Bridge (near the parking lot). It's a difficult unmarked scramble down the hill on the west side of the bridge and then up the gravel-cobble river to the terminus of the glacier. It's not a casual hike.

Kautz Glaciers.-- This glacier is viewed from Mildred Point in Van Trump Park. The trail is accessed from the parking for Christine Falls on Highway 706. It's a 3.5 mile hard trail to an overlook about a mile below the glacier terminus.

Tahoma Glacier.-- This glacier is viewed from the upper end of Emerald Ridge. The shortest way there is via the Tahoma Creek trail which is unmarked and not maintained as a normal trail, but used by backcountry rangers. It is a difficult 3.2 mile trail with places which cross the face of landslide slopes. Always check for the condition at the Longmire Visitors Center.

The other trails are the longer Kautz Creek trail (7.4 miles) or Indian Henry's trail (8.5 miles) to the suspension bridge over Tahoma Creek and to Emerald Ridge lookout point. These are the preferred or referenced trails since they are maintained with campgrounds available for longer (overnight) hikes.

Puyallup Glacier.-- This glacier is one of the most difficult to view since the West Side Road was closed at the Dry Creek trailhead. The glacier is viewed from Aurora Park on the Wonderland trail between the North Puyallup and Klaptche campgrounds. It's a difficult (long) 8.9 mile trail which offers a view of the terminus and whole Puyallup Glacier.

Carbon Glacier.-- This glacier is one of the few you can the closest view and access to a glacier. It is accessed on the Wonderland trail which goes alongside the east side of the glacier for over a mile to the Carbon River campground. The 8.6 mile trail is accessed from the parking at the Carbon River (NP) entrance to the Ipsut campground and then to the leg of the Wonderland trail.

Winthrop Glacier.-- The trail to this glacier is one of the other glaciers you can get a close view and access. It is accessed on the Wonderland trail from the Sunrise Visitors Center on the way to the Mystic campground. The 5.7 mile trail passes just past the terminus of the glacier and by Garda Falls.

Inter Glacier.-- This glacier is one of the smallest glaciers you can view from the Glacier Basin campground on the Glacier Basin trail from the White River campground. The 3.1 mile trail goes along the White River and forest to the alpine environment below the glacier.

Emmons Glacier.-- This glacier offer an overlook of the lower glacier and terminus. The 2.2 mile trail from the White River campground shares some of the trail to the Inter Glacier before splitting to the Emmons Glacier.

Fryingpan Glacier.-- This glacier is also one of the smallest glaciers you view from the Summerland campground. The 3.7 mile trail is part of the Wonderland trail starting about a mile west of the White River campground.

Whitman & Ohanapecosh Glaciers.-- These glacier are more a pair interconnected with the mountainous terrain. The trail is 2.5 miles beyond the Summerland campground (add distance from trailhead to there) to the overlook and 4.0 miles to Indian Bar campground.

Advisories

When viewing glaciers up close, you should respect the glacier, which are in constant movement and change and creating dangerous situations for anyone close. This is especially true near the terminus (end) of the glacier, where ice is breaking off. An advisory about glaciers.

Do not go on a glacier without experienced hikers or climbers and the proper equipment.

Glaciers are inviting to hike and explore. But they are dangerous for the inexperienced and ill-prepared hikers. Glaciers are very dynamic and constantly changing environments, so it's best to view and photograph them, but don't go on them without guides and equipment.

Another constant problem is the flow below a glacier where the diurnal flow varys as water in the glacier freezes at night and thaws during the day. This causes a cyclical flow in the river below the glacier. This effect extends later in the day going downstream. This is important if you wade across a glacer or snowfed-stream.

Use caution crossing glacier-fed streams and creeks and follow proper crossing technique.

A potential serious problem glaciers are outburst floods. This usually occur in late summer after extended warm periods, but not restricted to these factors. Outburst floods happen when a rapid melting or breaking occurs within the lower end of the glacier causing an extreme amout of glacial ice and material to flow downstream in a wave, such as happened in recent years on Kautz and Tahoma Creeks.

In short, be careful around the terminus of glaciers and in the river channel below glaciers. Be alert to unusual sounds and other signs and move immediately (laterally) up the valley in event of unusual sounds or conditions coming downstream. And always follow the proper crossing technique.

Resources

Below are resources for more information about the glaciers on Mount Rainier. The Carolyn Driedger book isn't currently available except at the Jackson Visitors Center at Paradise, Mt. Rainier NP.

- Books in Print

- "A Visitor's Guide to Mount Rainer Glaciers", Carolyn Driedger, PNNPFA, 1986.

- Books on Mt. Rainier

- Websites

Note.--Map on Web page from "A Visitor's Guide to Mount Rainer Glaciers", figure 1, page 7.

Please use the contact link to send e-mail.